“We ate dried peas that were destined for animals in the Schönbrunn Zoo. The peas had to be soaked overnight, and the next day countless worms floated on the surface of the water.” This is the memories from a girl from Vienna. Europe lies in ruins after six years of war. Hunger greets us daily and relentlessly. It was out of this need that the “Schweizer Europahilfe” (SEH) was founded in 1948, marking the birth of SWISSAID.

Today, 75 years later, war is raging again. It is destroying not only the infrastructure in Ukraine, not only human lives and hopes, but also progress in the fight against hunger. When the United Nations adopted Agenda 2030 in 2015, committing 193 member states to eradicate poverty and hunger for good by 2030, there was confidence. The efforts of NGOs like SWISSAID had made an impact: Fewer people were suffering from malnutrition. More and more people had access to water, education and medical assistance.

“Swiss Aid to Europe” was founded in 1948. This collaboration of Swiss aid organizations active at the time offered help to thousands of people in Europe suffering from the consequences of the war.

Multiple challenges

But the wind has changed. The war in Ukraine is also hitting the Global South hard. In addition, there is the climate crisis, which is increasingly reflected in the daily weather. Heavy rainfall is increasing. So are hot spells. Last summer, birds fell dead from the sky in India. In Niger, entire harvests were destroyed. Millions of people were left without food. In the meantime, 830 million people worldwide are again suffering from hunger. That’s one in ten people.

Blaise Burnier, Africa expert at SWISSAID, sees food security as one of the most pressing problems. Especially in the Sahel region. “Deserts are growing rapidly. Fertile land is disappearing. And this threatens the livelihoods of millions of small farmers. Add to that: Young people have hardly any prospects. That makes them susceptible to recruitment by militant groups and migration to the West.”

In addition to the repercussions of the war in Ukraine, there is the climate crisis and its dramatic consequences. In Niger, for example, where the drought has caused immense damage to the crops. The population has been seriously threatened by hunger. “The livelihoods of millions of farming families are under threat”, explains Blaise Burnier, Senior Regional Advisor for Africa at SWISSAID.

Tief anchors

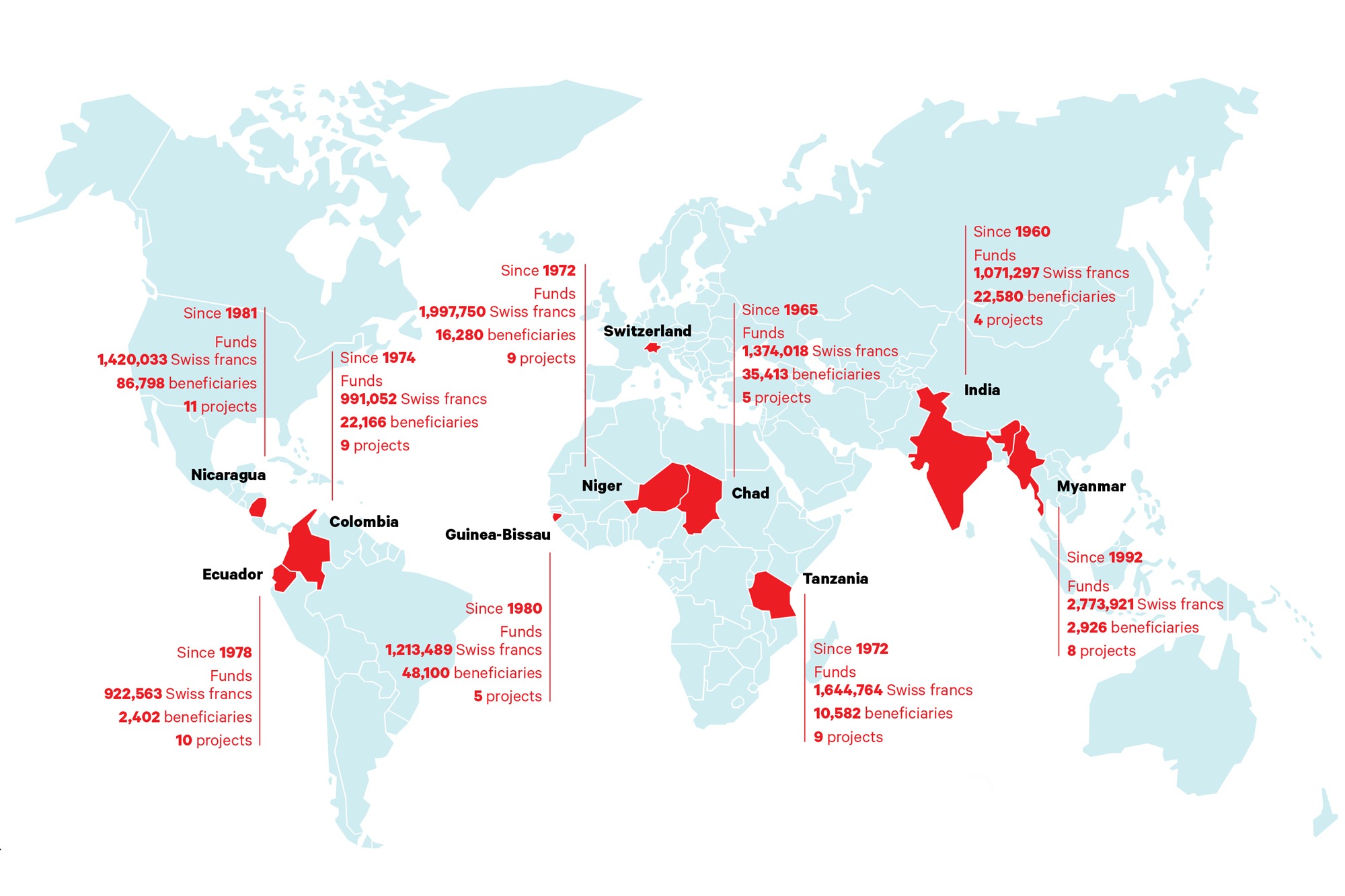

But what can an NGO from a small country like Switzerland do against these multiple crises? Of course, we cannot overcome the problems on our own, but we do pave the way for hundreds of thousands of people a year to a safe, healthy diet. In doing so, we benefit enormously from our 75-year experience. In Tanzania, for example, SWISSAID has been active for 50 years. In India, Chad and Niger, even longer. Most of the employees in these countries are local specialists. Since 1979 – as one of the first NGOs ever – SWISSAID has not relied on Swiss “guest workers”, but has recruited local men and women who know the country, the mentality and the people. Help for self-help, literally.

“We have a broad network in our nine countries and have long-standing, trustworthy partner organizations,” says Nicole Stolz, Head of Development Cooperation. “That gives us clout: we know what the needs are on the ground. And can react quickly. This helps us especially in emergency aid, which will become more important in the next ten years,” says Stolz.

The increasing number of disasters means that, in addition to long-term projects, much more short-term aid is likely to be needed, especially in the case of acute droughts and famine crises like the one in the Sahel last year. “With our network, we have the local support it takes to get food parcels or medicines quickly and efficiently to the people who need the help most.”

“We are broadly networked in our nine countries and have long-standing, trustworthy partner organizations,” says Nicole Stolz, Head of Development Cooperation.

Effective tool

With the profound experience in agroecology SWISSAID also has an effective tool. As long as 30 years ago, SWISSAID supported the smallholder movement “La Via Campesina” in Nicaragua Landless farmers there fought to obtain their own land and lobbied for more rights. Early on, we also began to operate local seed and grain banks, thus providing farming families with local seeds that are ideally suited to the climatic conditions.

In this way, smallholder farmers do not become dependent on the seed multinationals and can rely on their indigenous, hardy plants. “In the field of seeds, we now have a level of knowledge that sets us apart from others,” emphasizes Nicole Stolz. This is evident in projects such as Crops4HD a global program that promotes the production and consumption of resilient and local plant species. Here, SWISSAID works closely with the FIBL research institute and the Alliance for Food Sovereignty of Africa.

First milestone in new history

Such networks are likely to become more important in the future. The country managers are convinced of this. Whether in Colombia, Nicaragua or Niger, cooperation with universities, think tanks and research centers is working. The age-old approach of agroecology is being given new tools through technological progress. Useful data or information can be exchanged quickly. And women farmers can see for themselves the successful effects of agroecological cultivation even in more distant parts of the country.

The work does not stop in the project communities, but spreads further afield. And it does so regionally, nationally and internationally, at conferences or at the UN Global Food Summit. “SWISSAID is increasingly taking on the role of knowledge mediator and expert. After all, agroecology is a possible answer to the current crises that are looming ahead. More and more people and institutions are becoming aware of this.”

This is what is happening in Tanzania. There, agroecology now has a fixed place in the government’s agenda. Support for women smallholders and sustainable agriculture is thus institutionally anchored. Other SWISSAID partner countries could follow this example. Nicole Stolz describes it like this: “The fight against hunger is not a fight against windmills. The world is evolving. Together, we can influence the direction!”